AI Roundup: Current Barriers to AI Adoption

Fewer mistakes than humans, more mistakes than we're used to from computers.

An article on Engadget earlier this week mentioned that a chatbot that New York City launched for business users in the city was dispensing incorrect and possibly even illegal advice for those using it. Obviously, this is less than ideal, and being that you are dealing with the government and not a commercial entity, it can be that much more difficult to dig out of a mess created by AI. There is also less direct financial benefit from reducing human labor since government is not (unfortunately) bound by the same economic constraints as is private industry.

And this to me will be one of the greater barriers to overcome when it comes to widespread AI adoption. Being 80% correct when suggesting a movie or when writing code that will be reviewed by a human is a fine level of performance to aim for. But for other things like driving a car or giving out advice that can have legal ramifications, being wrong comes with big consequences. It remains to be seen if we will ever get to that point.

Of course, the other option is to allow for wiggle room in these areas. A self-driving car that reduces injuries and deaths by 99% over human drivers is still beneficial even if it means grappling with real-life trolley problems. Legislation can easily be modified to allow for easy appeals given proof of an incorrect or misguided session with a chatbot (but it would need to be as seamless as getting that refund).

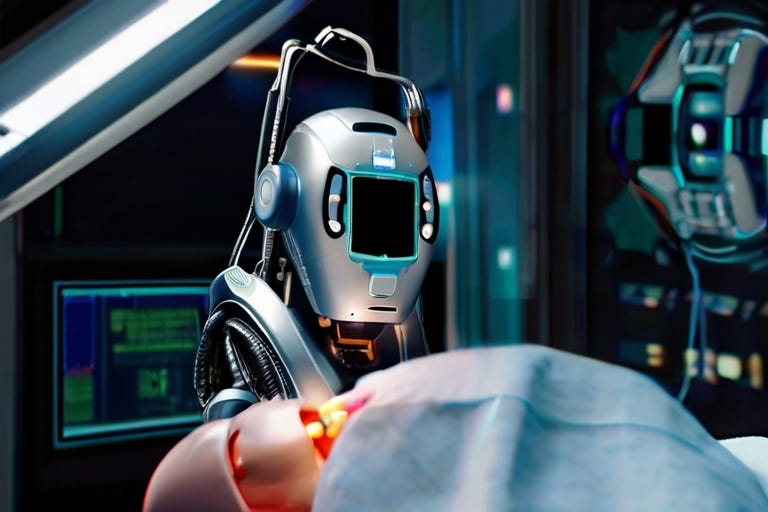

Another article that was making the rounds recently was regarding the use of AI in the medical setting and how AI systems are inclined to replicate inherent/deep-seated biases that exist in the system already (specifically in America). Now to me, AI is a great tool for overcoming these biases (putting aside garbage in/garbage out) since it is possible to overweight those populations that have biases and tell the AI to treat them with special respect. The health system could also benefit from flagging examples of these biases.

For example, her article mentions that many brain cancers are missed because patients are dismissed as having more likely symptoms (horses not zebras), but AI could easily bring into the conversation factors such as age and frequency of visits - across the entire healthcare landscape - to see where in the end brain tumors could in fact be a possible outcome (listen to this episode of Ear Hustle to hear a terrible example of this).

In summation, over the last 30 years of computer usage by the general public, we have become accustomed to computers doing the correct thing 100% of the time. Our paste always has what we copied; our emails always make it to their destination. In the effort to make our computers behave more humanly, we are going to need to spend a lot of time conditioning the public to realize that computers trained by humans are going to act like humans, though the possibility exists that they will make fewer mistakes in repetitive actions, such as driving a car or writing code. Time will tell.